– How it used to be in former times

by Otto Riesinger

Prenotation: “How it used to be in former times” is a series of articles written by Otto Riesinger and published in the half yearly publication of HLTOE society over several years. Most of the content is derived from Otto’s personal experience of decades of farm life and written in a very personal style.

I would like to tell you about the topic of hay and fodder harvesting for cattle and horse feeding in this article of our series “How it used to be in former times”.

The work of hay and fodder harvesting was often done completely by hand until the 1950s, just like many hundreds of years before. This was especially valid in the sloping region where I was born in the second half of the 1930s. Thus, I was able to experience this all and I also worked this way myself.

In this context, however, it must be mentioned that our meadows produced little yield in the 1940s till the 1960s. Some of them were therefore only mown once a year. At that time, there was simply no appropriate fertilization available. The little manure that was available was usually spread on the meadows near by the farm and the poor areas were then fertilized with pig manure and probably with potato tops in autumn and winter. In spring, this now dried material spread out in autumn was raked up again and reused as bedding in the cowshed, because there was always too little material for this purpose at this time of the year.

Earlier generations also irrigated their meadows if there was a small river in the immediate vicinity of the ground and the adjacent terrain was suitable. For this purpose, small ditches were dug in the layer line and the water was fed into them when necessary. These systems certainly had to be maintained on an ongoing basis. The efforts for maintenance may have been one reason why no one bothered with this method over time, although this type of irrigation would certainly have increased the forage yield.

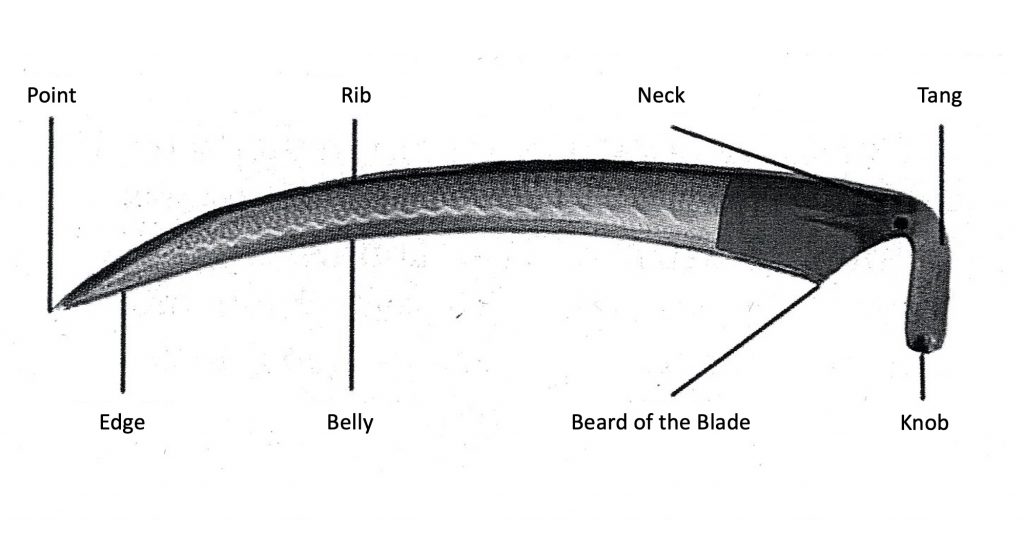

The hay and forage harvest starts by mowing with scythes. The scythe as a tool was an indispensable part of rural life until the advent of mowing machines. The first scythes were found before Christ. The origins of the scythe form in use today date back to the 12th century. These early scythes had already an edged back of the blade (Rib), from which a connecting piece emerged (Tang), to which a long wooden handle was attached. This made it possible to work in an upright position. Unlike in grain harvesting, the scythe played a decisive role in the development of medieval meadow farming. The scythe blade that is common today consists of the half centimeter wide cutting edge. This is the cutting part that has to be sharpened again and again with a whetstone and also needs to be cold-hammered regularly. Cold-hammering helps to resharpen the scythe for a longer period of time. Opposite the cutting edge is the scythe back (Rib). It serves to stiffen the scythe blade. Connected to the scythe back is the attachment with the adjustable scythe ring which connects the scythe blade with the long handle.

It was and is very important to set the scythe blade correctly to the handle and to the mower who operates the scythe so that it is in the right position to the ground and also has the right “forward grip”. In general, the scythe should also be specifically set to the mower so that satisfactory and energy-saving mowing work can be carried out. A good mower does not make jerky movements, but rather strives for a smooth, pulling cut. Both hands hold the wooden handles of the scythe and with great sensitivity he gives the scythe blade the right position to the ground.

The start of the mowing work after the winter was usually the daily mowing of green grass fodder for the cattle. The transition from dry fodder (hay), i.e. winter fodder, to green fodder always had to be done slowly and carefully so that the digestive organs of the cattle could adjust without major problems. It often became critical when the hay supply was already running out during this time, because it was particularly important to feed the cattle with additional hay during this phase. For centuries up to the present days, daily mowing of green grass or grazing on the pastures until late autumn was the essential basis of cattle feeding. It was with the introduction of silo farming that a radical change in cattle feeding occurred.

A certain tension was felt by all members of the farm when it was time to start mowing for hay-making in summer. The uncertainty whether the good weather would last for the next few days and whether there would be enough mowers and workers (day laborers) was always present during this time, especially when large areas of meadow had to be mown. The knowledge that strenuous working days are ahead also lead to tension. According to a description from my father a long time ago, mowing the meadows at that time began very early in the morning, sometimes before the beginning of dawn, around half past two, even if it was still quite dark. But the dewy grass was easier to mow than the dry grass. It also helped to avoid the heat of the day that began with the rising sun. People were happy to stop mowing when the heat of the day came.

When a mower noticed that the cutting edge of the scythe was weakening, he would place it firmly on the ground with the handle facing downwards so that it would stand securely. He pulls the wet whetstone out of the holder hanging on the waistband and, with quick movements of the right hand, sharpens the scythe blade, which was held in the left hand. The whetstone holder was usually filled with a little water and a tuft of grass so that the water remained calmer and the whetstone remained moist. The freshly mown gras was usually spread out with the scythe as the mower returns from the finished swath or women did this work immediately after mowing with the pitchfork.

Since the meadow grass was always dried on the ground, the hay that was being made could be turned over for the first time with the normal hay rake after lunch on the same day. On a sloping area, work was always carried out from bottom to top.

The aim was to use the rake to get an acceptable stack of dried grass and to turn it over with a jerk so that the already dry top side was at the bottom and vice versa, the still green bottom side was at the top. Depending on the weather and the condition of the hay that was being made, it was usually left lying for the next day and turned again with the hay rake in the morning. If the weather condition was still too wet, the half-finished hay was raked and then stacked with a fork towards the evening.

If it was only a thin layer of grass or the grass was already dried very well it was put to stacks already the first day after mowing. The idea was to protect the fodder from unnecessary moisture by the dew overnight and that moisture could also evaporate a little in the stacks. This “evaporation” had a valuable physical background. While the thinner and lighter leaves and plant parts dried out more quickly in the dry, hot air of a summer day and easily crumbled when being further processed, the thicker plant stems and leaves took much longer to dry out. In the stack, these dry plant parts absorb moisture overnight from the still more moist parts of the grass. This way the drying process gets more homogeneous for all components of the fodder.

The hay which had been stacked overnight, was spread out again the next morning after the ground was dry again. It was turned several times during the day with a pitchfork according to the drying status.

The hay was put into swathes in the afternoon and the swathes were gathered and brought to the barn. In case it was already dry grass when it was mown it was sometimes possible to mow in the morning and bring the finished hay home in the afternoon.

The hay cart drove along the swathes of hay – in my youth it was pulled by two oxen which suffered from the horsefly plague on these days. Although we always smeared them with horsefly oil or something similar, they were tormented mercilessly by these annoying beasts. So it was our job as children to fend off these annoying vermin with twigs from the nearby bushes.

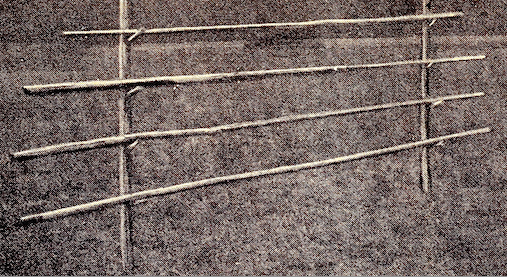

In case the weather was not suitable for haymaking for a longer time and the meadow intended for hay making was standing too long, the fodder was hung on stacks. Especially when fodder with many leaves such as clover was to be made into hay, it was best to stack it. The more often this fodder was handled during drying on the ground, the more valuable leaf mass crumbled off and remained on the ground, which meant considerable loss in the harvest. The various drying racks for stacking were particularly suitable for preventing this. The easiest to set up were the so-called hay huts, which were nailed together from thin poles, but the fodder had to be pre-dried for this method of stacking. With the so called “Swedish rider”, the fodder to be hung up can be taken fresh after mowing. A sub-type of this is the pole rider, which was often used in my region. They were also made from thin poles. But this method was added to the effort which began when setting up these stacks. The hay poles had to be hammered into the ground first. To do this, holes were punched in the ground with a hole punch, and the hay poles were then hammered into them. The hay poles were then filled one after the other with the prepared grass. It was important that the hung grass did not touch the ground so that no soil moisture could not rise to the hay. If the grass or hay was hung correctly and loosely, you could wait until it was dry without worry, even without sun, as the wind also dried it.

When the hay was really dry, regardless of whether it was ground-dried or rack-dried, you could start bringing it home. The most responsible job was “gathering” it on the hay wagon. I usually stood on the wagon and received the forkloads of hay brought up by the fork-worker with both hands. When the space between the side supports of the wagon was filled, I started laying it out above the side supports. When the wagon stood uphill, I started at the bottom corner at the back by laying down the first forkload, the next went to the opposite corner, the third to connect the two in the middle. This continued until we had usually loaded four or sometimes more layers. The height of the load was depended on the steepness of the area and the condition of the road home. Finally, the load was tied down with a pole. An iron link chain hung from the front end of the pole to the wagon where it was tied down at the front. A hemp rope was attached to the rear end and the pole was pulled down by this rope which was then fixed on the rear end of the wagon. The loose hay was finally cleaned off the hay load and then the journey home could begin. On slopes, uneven surfaces and dangerous bends, the hay cart had to be supported by one or two people with a fork or rake to prevent it from tipping over. This would be almost a disaster. Therefore there was a general sigh of relief, when such a hay load arrived safely at the farm gate. Everybody was relieved then, because transporting the hay load home did not always succeed.

Another strenuous task awaited the team at home, namely unloading the hay, lifting it up with forks and loading it into the hayloft. Several carts had to be brought in and unloaded on some days, especially when the weather worsened. In such cases, it could happen that it was already dark night before the work was finished. The last cart was then left overnight on the threshing floor until it was unloaded the next day. It was always a relief when the strenuous summer was over and the hay was under the roof.

The period of predominantly manual work in agriculture lasted almost until the end of the 1940s. When the economic situation slowly recovered after the end of World War II the mechanization of agriculture started slowly. Most farmers could hardly afford a major investment in the first half of the last century, due to the chaos of both world wars and the global economic crisis that began on October 25, 1929.

There were already very useful animal drawn machines for grassland cultivation at the beginning of the twentieth century. Picture 10 shows quite clearly how hay harvesting took place at the first stage of mechanization (the stage of animal-drawn machines). The mower shown was a great work relief for that time. However, there were problems with harnessing oxen, which were widely used as draft animals. The oxen were consistently too slow for the ground-driven mowers.

The drawn fork tedder was also very popular, because it relieved farm people from two or three times a day turning hay with forks. It was easy to operate, required little power and saved a lot of manual work and manpower. The same applies to the hay rake shown. Another advantage of these two machines was that they could still be used with the first tractors until more modern equipment could be purchased.

These are my memories of hay harvesting. Yours Otto Riesinger

Some remarks on the author Otto Riesinger:

He was born in mid-January 1937 and attended school from 1943 till 1951. Later on he attended an agricultural college and got the agricultural master´s examination in 1964.

He lived and worked on the farm of his parents most time of his life. After his marriage in 1970 he took over the farm.

He handed the farm over to his oldest daughter in the late 1990s but he was still active on the farm. In addition he dedicated also more time to his private museum and to writing about agricultural history after the handover.

Sources of Pictures:

Pictures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13: private archive Otto Riesinger

Picture 10: Lanz Brochure (Archive HLTÖ)

Picture 12: private archive Karl Krischka