Utilitarian harnessing methods are invariably the pertinent expression of an activity (agricultural, industrial, commercial) in a particular environment (that may be economic, geographic, technical and cultural, all at the same time).

Innovation has been a permanent feature over the last 2500 years and applies to material (harness, vehicles, tools), zootechnics, architecture, urbanism, agronomy… Over the course of time, techniques and know-how have developed, converged, been substituted one for another, or traveled (with population movements, itinerant apprenticeships, trade) and have survived in niche environments.

These parameters lend the subject of “animal draft” a patrimonial dimension that, above all, calls for a dynamic approach.

Long neglected by historians and many museum keepers, the heritage/s of animal draft “à la française”, bearers of testimony to the needs, tastes and the know-how of their time, generally partake of a paradox: a past wealth and prestige equaled only by how little is now known of them, and their present fragility.

An erroneous assumption long sealed the fate of working vehicles and harness: since they seemed to be ubiquitous, they were once believed to be of unlimited availabity, whereas, very few of these objects, cumbersome and hard to handle, difficult to engage the public with, have actually made their way into museums. How many were abandoned, broken up and burned? Today, how many of them stand there as decoration for round-abouts, how many others are used to show off logos (including for museums)?… All of them are condemned to disappear in the near future.

Conserving them, however paramount this is, cannot be the only thing we must do. When they stand alone and anonymous, these objects lose all meaning, and we know that, as far as heritage is concerned, not understanding something makes it very fragile. For all the objects that some collector’s benevolence managed to spare, there is now the whole issue of documentation.

Just regretting the immense losses will not change anything and the many artistic and archive traces can – at least partially – come to our rescue.

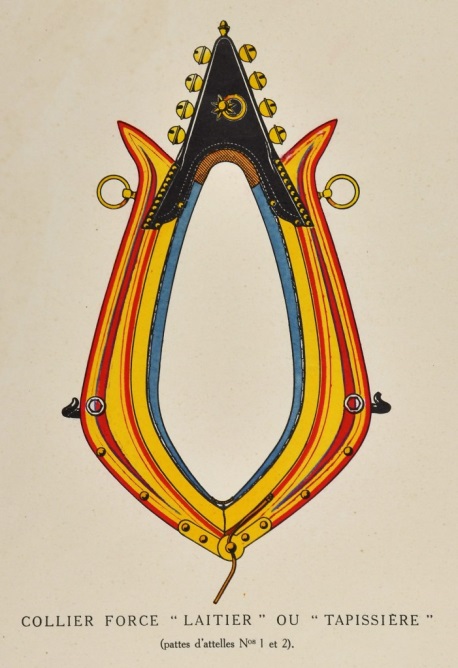

Taking into account the type of vehicle or equipment pulled, the nature and number of animals harnessed, the way they are arranged, the harness utilized, the way they are driven, and various accessories, I estimate at around 400 the number of traditional utilitarian harness methods at work in Metropolitan France at the beginning of the 20th century… (60% are rural, 50% of those concern transport).

The backward image of animal draft was often due to the fact that the last everyday harnessing methods, as they were at the time, generally did not take into account the latest progress (in questions of harness-making, for example, a field that was highly innovative right up to the inter-war period).

We must not indulge in hasty criticism, however. Thanks to people passionate about transmission, committed professionals still make it possible to envision a future with animal draft, especially in responsible farming developments.

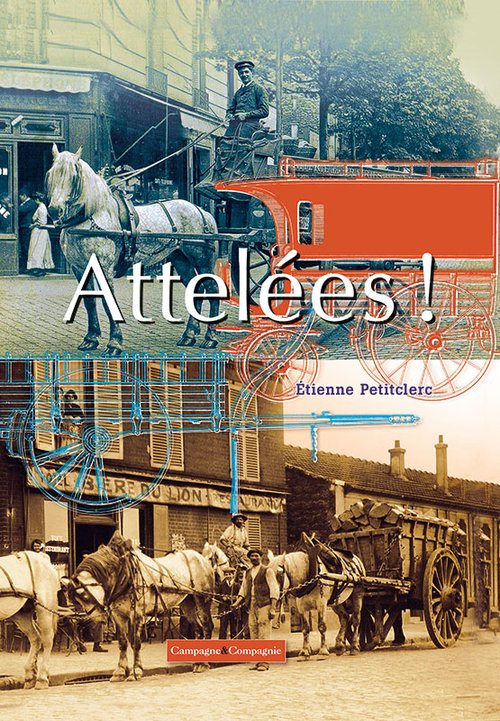

Born in 1972, Etienne Petitclerc trained as a historian and has been an archivist for twenty years. Fascinated since childhood by draft horses, he began early on to study traditional gestures and know-how in stock-breeding and using working animals, through fieldwork and meetings. He is a handler, collector, independent researcher and his knowledge and documentation efforts have enabled him to take part in many international juries and regularly appear as a lecturer. He is the author of some fifty papers and two books on the French heritage of animal draft.

The full-length article is available online in French and English under the title Petitclerc Traction animale et patrimoine Animal draft and heritage (long) at https://www.agriculturalmuseums.org/news-2/aima-newsletters/