Editor’s Note: In our continuing series on yoghurt and related food products, we can now set off to Greece with Evangelos Karamanes through the kind help of Irina Stahl of the Ritual Year Working Group (part of the S.I.E.F. https://www.siefhome.org/wg/ry/).

Greek yogurt has gained significant renown in international markets over the past few decades as a staple of a healthy diet. The international public was introduced to Greek yogurt primarily through tourism in the post-war era, often enjoying it for breakfast or as a dessert served with honey (or spoon sweets), along with almonds, walnuts, or dried fruits. From what I recall, in the 1980s and early 1990s, Greek yogurt, meaning strained cow’s yogurt produced by Greek milk industries, along with olives and olive oil, was among the few Greek products available on supermarket shelves in major cities in both the West and East.

Yogurt has a slightly acidic and pleasant taste, making it a popular and easily digestible food with excellent nutritional value. It is produced by coagulating fresh fermented milk with the addition of lactic acid bacteria.

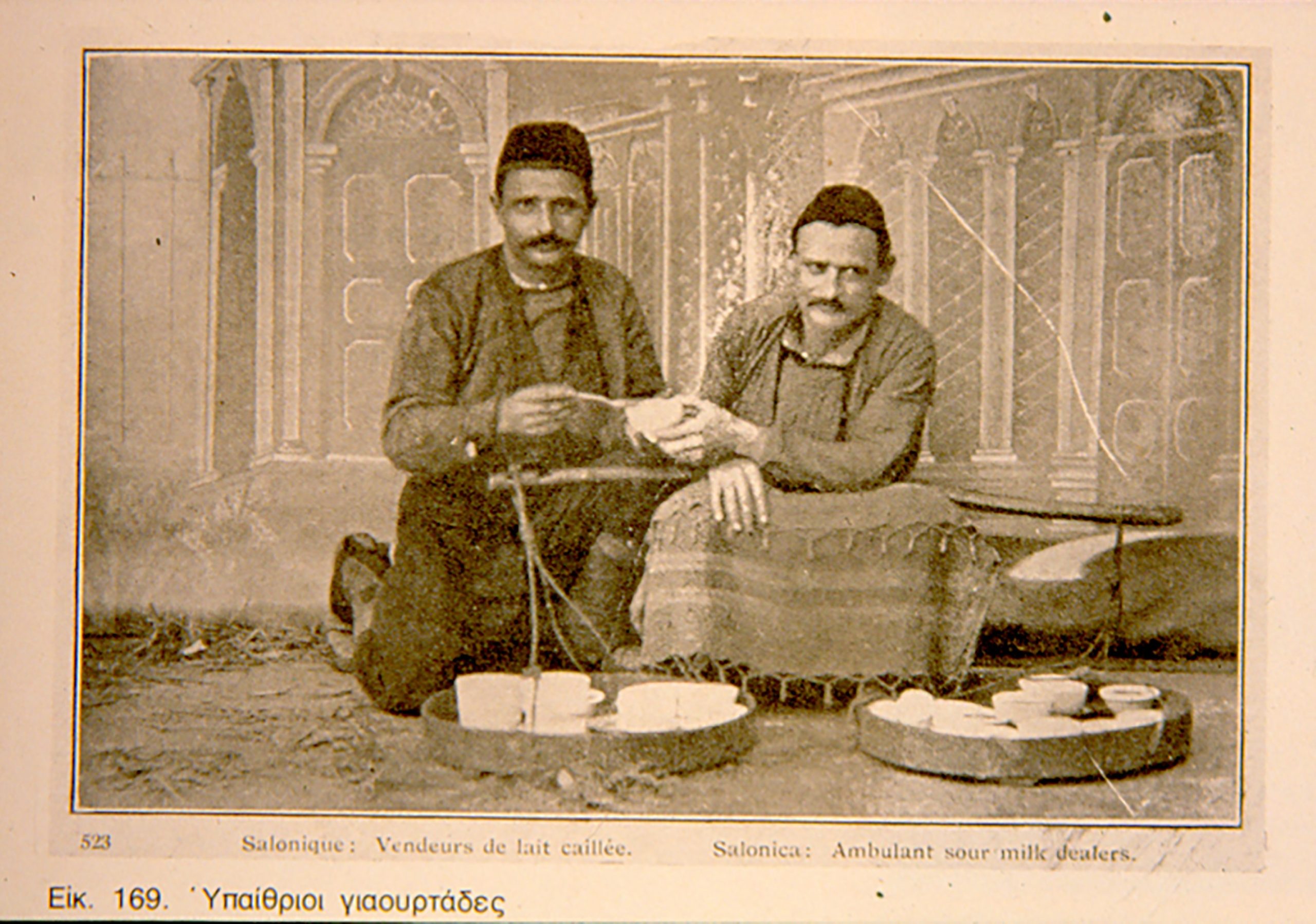

Fig. 1. “Ambulant sour milk dealers” (ghiaourtades) in Thessaloniki (Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace) www.searchculture.gr/aggregator/edm/LEMMTH/000043-11533_9643

In Greece, it is commonly known as “ghiaourti” ((jaúrti, γιαούρτι, το) or by its diminutive form “ghiaourtaki” (γιαουρτάκι, το). It is deeply ingrained in modern Greek diet and popular culture. A well-known Greek proverb says, “Whoever was burned in the porridge / in the soup / in the milk, also blows the yogurt”, which means that due to a past failure, one takes precautionary measures even when they are not necessary. The verb “ghiaourtono” and the noun “ghiaortoma” refer to the act of throwing yogurt at someone as a strong sign of disapproval. This act was common during the youth revolt in the 1960s and is still employed by protestors and activists in Greece today, as frequently reported in the news.

Yogurt has long had a place in popular tradition and tales, for example, Karaghiozis, a famous character from the shadow theatre, depicted as a yogurt seller in the cover of a popular booklet published in Athens around 1924-1925. In the Athenian Greek context, Karaghiozis represents a lazy, perpetually hungry, marginalized, poor, and oppressed city dweller who struggles to survive with his family. In his role as a yogurt seller, he consumes all the product with the assistance of his famished family and friends. Eventually, a small dog takes the place of yogurt, leading to the hero being beaten by disappointed customers and creditors.

Fig. 2. Karaghiozis (Library of the Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens).

The name “ghiaourti” is derived from the Turkish word “yoğurt” (see Bulgarian “yagurt” and Romanian “iaurt”). In Byzantine Greek, this type of dairy product was known as “oxyghala” (acid milk) preserved to this day in many Greek idioms. The name of street vendors in byzantine Constantinople “oxyghalatas”, was mentioned by the 12th-century poet Theodoros Prodromos (Ptochoprodromos) [Εάν ήμουν οξυγαλατάς, οξύγαλον να επώλουν (Προδρ. III 176) in a passage much discussed by philologists. Yogurt is called “xyghala” (’ξύγαλα, οξύγαλα) in Pontian Greek idioms and in Eastern Thrace, “oxyno ghala” (όξυνο γάλα) in Cappadocian dialect of Aravani, “xynoghalo” (Lesvos island, northern Aegean), “xyno” (Thrace), “(e)xyali” (Anafi, Cyclades), “axyalos” and “xyali” (Rhodes, Dodecanese), “ghala oxynon” (Lemessos and Paphos province, Cyprus, in Nicosia it is called “ghiaourtin”), and “xynoghala” in Mani, Peloponnese. It is called “ghighourti” in Crete, “ghiarghouti” in Arcadia, Peloponnese, and “dghiargouti” in Kynouria, Peloponnese. The Greek Vlachs of the Pindus Mountains refer to it as “markatu”. Pontic Greeks produce also strained yogurt known as “yliston”.

Dairy products obtained through the fermentation of lactic acid in milk have a long history in Southeast Europe and have been influenced by the political contexts of both the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires.

Fig. 3. Homemade yogurt from sheep milk with “skin” in clay pot (Vamvakofyto, Serres, Eastern Macedonia, Archive of the HFRC, 5050/2009, p. 201).

The basic process of small-scale yogurt production is well-documented in numerous ethnological and agronomic sources. Homemade yogurt preparation is widely practiced throughout Greece and shares similarities with methods used in neighboring countries. I will describe the process as performed by my mother in my native village in the Larissa area of Thessaly, Central Greece. My mother receives fresh sheep’s milk (goat milk is not preferred for yogurt) from one of the village shepherds, usually around 2-3 kilos each time. She pours the milk into a casserole, filtering it through a muslin cloth (tsantila) or a fine sieve. She then boils it for approximately 5 minutes to pasteurize it.

The milk is transferred to a clay, metal, or sometimes plastic pot (commonly known as “tupper” in modern Greece). When the temperature allows her to hold her finger in the milk for a count of 15 (around 45°C), she adds the prepared yogurt starter to the milk. The starter, known as “pitia”, “diaourtosporos”, or “maghia”, consists of yogurt mixed with two ladles of milk that have been warmed to a mild temperature. To prepare the starter, she always saves a portion of yogurt from a previous batch or purchases a pot of “ghiaourtaki” from the market, made from sheep’s milk and with the “skin” on it, avoiding strained cow milk yogurt. She gently mixes the starter with a fork, ensuring it is well incorporated. The pot is then thoroughly covered with a cotton towel and a blanket to retain the heat. She allows the mixture to rest for 2.5 hours. Afterwards, she places it in the refrigerator for one day before consuming the yogurt.

Fig. 4a and 4b. Homemade yogurt from sheep milk with “skin” in clay pot. The pot is covered with a cotton towel and woolen woven blanket to retain the heat. Marina Diamantopoulou, Mnimes ke gefseis tis Gortynias (Memories and tastes from Gortynia, Peloponnese), Athens 2022, p. 324.

In the traditional rural Greek context, yogurt was predominantly made and consumed during the period of abundant seasonal milk production, which typically occurred from early spring to summer. In rural communities, nearly every household owned sheep and goats, and family members took care of them throughout most of the year. In pastoral and mountain communities, larger flocks were tended to by specialized shepherds from springtime until July. Following the Greek Orthodox calendar, the consumption of yogurt held significant importance during specific religious occasions. One such event is Cheesefare Sunday (Tyrini or Tyrofaghou) and the week preceding it, which marks the last day before the Lenten fast (Sarakosti) for Easter when dairy products can be consumed. Additionally, yogurt is a customary part of Easter Sunday (Pascha) and the festivities of the Renewal (Bright) Week (known as Διακαινήσιμος Eβδομάδα in Greek), the 1st of May (Protomagia), and the Feast of the Ascension of Jesus Christ, celebrated on the fortieth day after Easter. Based on my field experience in mainland Greece, particularly working with transhumant shepherds and dairy food production, yogurt is highly valued and commonly enjoyed alongside roasted lamb on the spit during these festive occasions.

During the Ascension and other springtime celebrations, wealthy chief-shepherds (tselingades) who owned thousands of animals would distribute their daily milk production to the community as a customary gesture. Springtime was indeed a challenging period, especially for mountain villages that relied on the return of transhumant flocks from the plains to fulfill their needs. Yogurt was also consumed during seasonal sheep shearing. Moreover, ethnografic records indicate that yogurt was included in the meals served during childbirth and funeral ceremonies.

In the modern Greek context, the majority of people purchase their yogurt from supermarkets or specialized dairy product shops. However, homemade yogurt production is also practiced, particularly in rural areas. The preferred choice among Greeks is yogurt made from sheep’s milk, using the previous day’s yogurt as a starter, and covered with the “skin”. This type of yogurt is produced by milk industries as well as numerous farms.

Fig. 5a and 5b. Yogurt from sheep milk with “skin” sold in clay pot produced in Attica (a, b) (photos EK).

Strained yogurt, typically made from cow’s milk, holds a significant share in the market and is produced by industries using centrifugation to remove whey. A considerable portion of the strained yogurt production is dedicated to the making of tzatziki, especially during the summer months, by adding cucumber, garlic, dill, and olive oil. Production of strained yogurt in muslin bags is recorded by folklorists both in the islands and mainland Greece and is described by agronomists since the first decades of the 20th century (ghiaourti tis sakoulas, estraggismenin ghiaourtin, “yliston” in Pontic Greeks).

Fig. 6a and 6b. Popular brand of strained yogurt from cow’s milk produced by milk industry (a, b) (photos EK).

It became famous since the mid-1970’s when FAGE Company launched its brand “Total” of strained cow milk yogurt. Generally, a wide variety of yogurts are available, including different fruit flavors and those enriched with probiotics. However, plain yogurts made from sheep, cow, and to a lesser extent, goat milk, remain the most popular choice among consumers.

Author: Dr Evangelos Karamanes, Research Director, Acting Director,Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens

Sources

Anagnostakis, Ilias – Papamastorakis, Titos, «Αγραυλούντες και αμέλγοντες» (Living in the countryside and milking) in I istoria tou ellinikou galaktos ke ton proionton tou (History of Greek milk and its products), Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation, Athens 2008, pp. 211-237.

Imellos Stephanos, D.– Polymerou-Kamilaki Aikaterini, Paradosiakos Ylikos Vios tou Hellenikou Laou (Erotimatologio), (Traditional Material Culture of the Greek People – Questionnaire), HFRC, Academy of Athens, Athens 1983.

Karamanes Evangelos, “The shepherd’s crook”, Etnográfica, Número especial, 2022, eds. Cyril Isnart and Octávio Sacramento, pp. 47-52. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etnografica/12669; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.12669

Karamanes Evangelos, « Fêtes et lieux du calendrier populaire grec : inventaires et approches contemporaines des pratiques festives » in L. S. Fournier (dir.), L’inventaire des fêtes en Europe, L’Harmattan, Paris 2017, pp. 67-87.

Karamanes Evangelos, “Changes in Cheese Production Among the Koupatsaréï: the Cheese Batzos” in P. Lysaght (ed.), Food from nature. Attitudes and Culinary Practices, (Proceedings of the 12th Conference of the International Commission for Ethnological Food Research, Umeå and Frostviken, Sweden, 8-14 June, 1998), Uppsala 2000, The Royal Gustavus Adolphus Academy for Swedish Folk Culture, pp. 287-296.

Karamanes Evangelos, « Division culturelle du travail et construction identitaire dans le Pinde septentrional : le cas des Koupatsaréï (Département de Grévéna, Macédoine occidentale, Grèce) » in T. Dekker, J. Helsloot, C. Wijers, (eds.), Roots and Rituals. The construction of ethnic identities (Selected papers of the 6th SIEF conference on ‘roots and rituals’, Amsterdam 20-25 April 1998), Amsterdam 2000, Het Spinhuis, pp. 53-66.

Kechagias Christos, «I ghiaourti meso tis ellinikis istorias kai paradosis» (Yoghourt through Greek history and tradition) in I istoria tou ellinikou galaktos ke ton proionton tou, Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation, Athens 2008, pp. 503-515.

Megas Georgios A., Hellinikai eortai ke ethima tis laikis latreias, Athens 1956. Also published in English: Greek Calendar Customs, Athens 1958.

Wace Alan J. B. and Thompson Maurice S., The Νomads of the Balkans, London 1914.

Zygouris Nikolaos P., I viomichania tou galaktos (The milk industry), Athens 1952.

Journals

Laographia. Bulletin de la Société Hellénique de Laographie, vols. 1-44, 1909-2020.

Annual of the Folklore Archives / Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens, vols. 1-36, 1939-2019 [www.kentrolaografias.gr and the digital repository

http://editions.academyofathens.gr/epetirides/xmlui/handle/20.500.11855/2 ]

Digital Sources

Greek national aggregator for digital culture content: www.searchculture.gr

Digital repositories of the Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens: www.kentrolaografias.gr, repository.kentrolaografias.gr/xmlui/

Dictionary of the Academy of Athens (Χρηστικό Λεξικό της Ακαδημίας Αθηνών): https://christikolexiko.academyofathens.gr/

Cyprus food virtual Museum: http://foodmuseum.cs.ucy.ac.cy/

Gate for Greek Language: https://www.greek-language.gr/

Figures

- “Ambulant sour milk dealers” (ghiaourtades) in Thessaloniki (Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace). www.searchculture.gr/aggregator/edm/LEMMTH/000043-11533_9643

- Karaghiozis, a famous character from the shadow theatre, depicted as a yogurt seller in the cover of a popular booklet published in Athens around 1924-1925. In the Athenian Greek context, Karaghiozis represents a lazy, perpetually hungry, marginalized, poor, and oppressed city dweller who struggles to survive with his family. In his role as a yogurt seller, he consumes all the product with the assistance of his famished family and friends. Eventually, a small dog takes the place of the yogurt, leading to the hero being beaten by disappointed customers and creditors (Library of the Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens).

- Homemade yogurt from sheep milk with “skin” in clay pot (Vamvakofyto, Serres, Eastern Macedonia, Archive of the HFRC, 5050/2009, p. 201.

- Homemade yogurt from sheep milk with “skin” in clay pot. The pot is covered with a cotton towel and woolen woven blanket to retain the heat. Marina Diamantopoulou, Mnimes ke gefseis tis Gortynias (Memories and tastes from Gortynia, Peloponnese), Athens 2022, p. 324.

- Yogurt from sheep milk with “skin” sold in clay pot produced in Attica (a, b) (photos EK).

- Popular brand of strained yogurt from cow’s milk produced by milk industry (a, b) (photos EK).